By Sloane Song

Due to the concern of government repercussions, the writer of this piece writes under the pen name “Sloane Song.” Human Rights in China has independently verified the identity of the writer.

December 26, 2023 marked the fourth anniversary of “12·26 Xiamen Gathering Case,” in which lawyer Ding Jiaxi was arrested. On this occasion, Human Rights in China is releasing a serialized feature dedicated to Luo Shengchun, a human rights advocate, as a tribute to her unwavering efforts. This feature acknowledges her relentless dedication to seeking justice for Chinese prisoners of conscience, including her husband, Ding Jiaxi, and advocating for human rights and freedom for the Chinese people. The feature will be divided into five parts, unveiling various facets of Luo Shengchun. A special thank you to Luo Shengchun for generously sharing intimate details of her life, allowing us to see her not only as a courageous and conscientious civic activist but also as a wife, a mother, and a woman with voice and attitude.

This piece will be published by Human Rights in China one part at a time, over five weeks.

Writing in her diary on April 23, 2014, Luo Shengchun imagined how a “great wife” would write to her imprisoned husband:

“Dear husband, you don't know how much your influence has changed me. I have now become a New Citizen advocate. I help organize your recordings and share them. From your recordings, I have gained a deeper understanding of your ideals of a civil society. You are gradually transforming me from a woman who only knew about romance into a woman who cares about society, who has ideals and a broad mind, and who shares the worries of the world and rejoices in its joys... I will continue to support you, understand you, until the day you are released.”

Luo believed that this “great wife,” with devotion to a democratic China, was the opposite of herself, a “little woman.” When Luo left China with her two young daughters and arrived in the United States in 2013, after her husband Ding Jiaxi, a human rights lawyer and one of the leading figures in the New Citizens Movement who was sentenced to three and half years in prison, she thought only by suppressing her emotions and conforming to her husband’s expectations could she be the “great woman” with ideals for her country and civil society.

During her early years away from her husband, Luo saw herself as a “little woman,” confined to the realm of affections and romance. In those days, when she corresponded with Ding, her letters were imbued with her sorrow and bitterness, with words like “you always tell me to love you in the way you like, and I have done that, and I’ve been doing that for many years. But have you ever thought about loving me in the way I like, even just once? I don’t need it for a lifetime, just one time, a real one...”

Nine years later, on April 29, 2023, three weeks after Ding was sentenced to 12 years in prison for “subversion of state power,” and his New Citizens Movement peer, Xu Zhiyong, a legal scholar, was sentenced to 14 years in prison, I met Luo at Democracy Salon in New York. Later, in June and July, I interviewed her at her apartment in Virginia, and Luo shared with me her correspondence with Ding. Luo told me that she still deeply, painfully loves and misses Ding, but her world is now much bigger than that. “I believe I’m standing on the same level as he is now,” Luo said. “I am determined to continue the cause of my husband and Xu Zhiyong. I’m determined to be a woman with a voice and attitude, be a real citizen!

Now, Luo’s only question is how to bring her Jiaxi back home to the US from the dictator’s regime, from the CCP (the Chinese Communist Party).

I.

Luo Shengchun’s husband, Ding Jiaxi, now 56 years old, is a prominent human rights lawyer in China. Born and raised in a humble village in Hubei Province, Ding initially pursued a career as a jet-engine engineer after attending Beihang University, a prestigious science and technology institution in Beijing. While in college, he joined the 1989 Democracy Movement and identified with the concepts of anti-corruption and democracy, but was called back to school by his teacher for finishing an urgent paper on the night of June 3, when the violent crackdown unfolded.

After working in an aircraft engineering institute, Ding returned to Beihang University to pursue post-graduate studies, where he met Luo in 1992. It was during this time that he developed a keen interest in law, and dedicated his spare time to self-study. After passing the bar exam in 1994, Ding started his professional career as a lawyer with a concentration on civil law. In 2003, he founded his own law firm, Dehong.

Luo recalled that as a commercial lawyer, Ding lived large. He used to spend 100,000 CNY on golf per year, enjoyed five-star hotel stays, and ate expensive dishes such as bird nest soups and abalone.

Being a successful lawyer not only brought Ding comfortable living conditions, it also exposed him to the injustice in society. By the time he attended Fordham University School of Law in the United States as a visiting scholar, he had already developed a strong determination to dedicate himself to the social movement in China. This period provided him with the opportunity to engage in discussions with fellow scholars. Upon his return, he had transformed into what Luo referred to as a “veteran angry youth.” He became increasingly disheartened by the lack of freedom of speech and the injustices prevalent in the social news he encountered. Meanwhile, Ding collaborated with human rights activists and legal scholars, such as Xu Zhiyong, in the New Citizens Movement, and embraced the principles of the New Citizens Movement: Freedom, Justice, and Love.

In 2013, Ding was detained as part of a widespread crackdown on activists and lawyers in China, charged with “gathering a crowd to disturb public order” and received a three-year and six-month prison sentence. After his release, in the fall of 2017, Ding visited Luo and their daughters in the States for two months. On December 26, 2019, Ding was arrested again, and in April 2023, he was sentenced to twelve years in prison for “subversion of state power.”

The above paragraphs summarize the story of Ding Jiaxi, a prominent defender of human rights in China, the beloved husband of Luo Shengchun, her “only one in this life.” It is a narrative that Luo has recounted to journalists time and time again, a story that journalists have requested from her over and over again, a tale in which she only exists as a supporting character, yet this story has come to define her very identity.

To comprehend Luo Shengchun, her love for Ding, and her personal journey, one must not leave out the chapters of Ding’s story. Yet, that is only one fragment of Luo’s own narrative, in which she stands as Luo Shengchun first, before ever being known as Ding’s wife.

II.

“The more I understand Jiaxi and his ideals, the deeper I love him,” Luo Shengchun told me. “Our love started as corporeal and affectionate, yet it has transformed into a spiritual connection. I felt the purpose of life when I was around him, whether as a wife or a mother of our kids. I didn’t know who I was before, but now I see clearly who I am meant to be: a person with a sense of responsibility for society, who is passionate, willing to sacrifice, who carries a mission.”

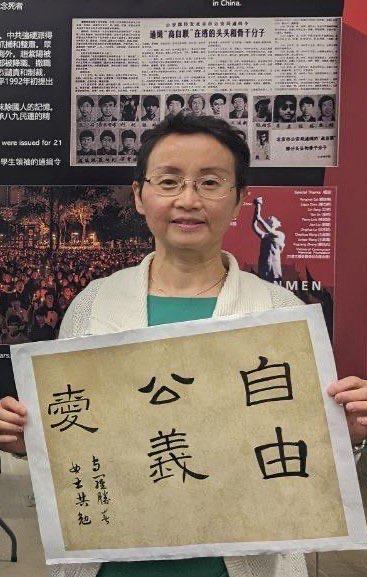

April 29, 2023, New York. At the memorial museum of Tiananmen Square massacre, after a seminar about Xu Zhiyong, Ding Jiaxi, and the Citizens Movement that promotes freedom, righteousness, and love in China.

Luo Shengchun, aged 55 this year, stands at just over 1.5 meters tall and weighs less than 130 pounds. With short curly hair, long and slender eyebrows, she always smiles with her eyes. On important occasions, she applies makeup, outlines her eyebrows, and puts on lipstick. She wears 5-centimeter-high black high-heeled shoes to exude a stronger presence, yet she often complains about how painful these shoes are to walk in. She enjoys practicing yoga and swimming. She has a fondness for the crispy skin of chicken and duck, considering them incredibly succulent. She also savors Mediterranean cuisine, using the complimentary pita bread to dip into olive oil and various spices whose names she can’t quite recall. In her home, the floors are made of wooden planks. She delights in the feelings of walking barefoot on them during the summer. When we conduct interviews, she takes the time to brew a pot of green tea, peel a pear, and settle into the single armchair opposite me. She sways gently, one foot resting on the chair, wrapped in a blanket.

Throughout the interviews, Luo’s voice occasionally faltered when she spoke about her two daughters. She told me that she sometimes found a semblance of her daughters reflected in my presence.

III.

In the fall of 1992, at a thermophysics experiment lab at Beihang University, the 24-year old Luo Shengchun met the 25-year old Ding Jiaxi. She was in the lab struggling with her thesis when Ding walked in with “the most captivating, sunny smile” she had ever seen. For Luo, it was love at first sight.

“Hello, shi jie!” Ding warmly greeted Luo. In China, shi jie, which literally means academic senior sister, is a respectful way to greet a female student who goes to the same school but in a higher grade.

Luo felt like that was something intimate, genuine in his smile that she hadn’t seen in the smiles of others. Not a polite smile like a mask, but a kind of sincerity she could touch and trust. “I was completely melted by his smile,” Luo recalled.

Luo started her graduate studies in the field of biomedical engineering at the Department of Engineering Thermophysics at Beihang University two years earlier than Ding. She identified herself as a person “depressed by nature, introverted and pessimistic” at that time.

Outside of the laboratory, the 24-year-old Luo Shengchun was in her prime. Boys from other schools frequently visited her, and Luo would take them out for meals, though she never accepted any of them as her boyfriend. When Ding Jiaxi returned to Beihang University for his graduate studies in 1992, their mutual advisor warned him, “Be cautious when approaching Luo Shengchun; she already has a legion of admirers.”

Shortly after their first encounter, Ding started to passionately show his affections for her. She was head over heels for Ding, but she didn’t want him to know, so she presented herself as a reserved shi jie in front of him. He sent her flowers, bundles after bundles of roses, and wrote her many love poems, which Luo found adorable but at the same time, tacky. He invited her out for meals or to go skating, and Luo would suppress her excitement and turned him down a few times before she said yes. He showed up in her lab and around her dorm all the time with different excuses, and while she pretended to ignore him, she in fact wouldn’t be able to concentrate on her work. Whenever she was around him, she felt like “my heart would flutter like a startled deer.” Luo guessed that to some degree, he must have known her feelings for him too.

Ding and Luo started dating during the winter break, and from then on, their relationship blossomed into a carefree young love. When spring arrived and the new semester began, Luo would often sit behind Ding on his bicycle with her arms wrapped around him. Ding would be by her side, keeping her company through the late nights of paper writing.

In February 1993, Luo began working at the 304 Institute of National Defence Industrial Department. She wholeheartedly supported Ding, who aspired to a career as a lawyer at the time. Despite Ding’s limited availability for dates, simply being around him made Luo happier than ever. Once a melancholic person, Luo found herself crying less, laughing more, and more willing to go out and meet new people.

“Jiaxi completely changed my whole outlook on life and the future,” Luo said at the 14th Annual Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy in 2022. “After we began dating, my college friends barely recognized me, as Jiaxi brought out the sunshine in me.”

IV.

In 1968, two years into the Cultural Revolution, Luo Shengchun’s mother wanted to have an abortion. She was 39 years old, and her husband had just been sent to a farm for “labor reform.”

By then, Luo’s mother was already raising four boys and a girl on her single salary as an accountant in a rural village. She didn’t know how she could support one more child in the family. But as she stood in front of the hospital, she decided to keep the baby. What if by some stroke of luck, she wondered, the higher-ups decide to show a bit of kindness, considering the newborn baby and sparing Luo’s dad from being sent so far away?

In October, Luo Shengchun was born in Jiangxi Province. Her birth didn’t change her father’s fate of working in a labor camp, living in a a foul-smelling cow shed, on the verge of suicide, Her mother single-handedly shouldered the household responsibilities. When her father made occasional trips home for a day or two during the Spring Festival, he would sit with her under the covers to read poetry from Tang and Song dynasties together.

Luo understood her mother was going through a lot. At the start of the Cultural Revolution, her sister forcefully had half of her hair shaved off, a common practice back then to humiliate people. One of her brothers was denied the opportunity to attend junior high school. Another kid once taunted him for being a “labor reformed prisoner,” he erupted into a fit of rage and almost beat the boy to death. He was then diagnosed with bipolar disorder, often running away from home and relying on pills to fall asleep. Luo’s mother wept day and night for him, traversing twenty kilometers on foot to retrieve his medication from the hospital as she couldn’t afford a bus ride .

All the other women in the neighborhood appeared to have many friends and were always chatting, yet her mother was isolated. Night after night, she returned home after long hours of work, hastily ate dinner, and then continued her side jobs to support their family of seven. Luo thought her mother must be sad and lonely. Sometimes, she wondered how her life would be different if she had been born into a different family.

Amidst an era engulfed in political fervor throughout China, Luo gradually grew up. She used to cry a lot for reasons she can no longer remember. She could sense that certain aspects of her life lacked meaning and coherence, feeling small and inconsequential in the vast expanse of the world. What is my purpose in this world? she wondered. She couldn’t find an answer, and she was always a bit unhappy.

“The melancholic temperament within me was ingrained since the time I was in my mother’s womb, a product of her longing for my father during the Cultural Revolution.” Luo wrote in her diary on February 25, 2014. “Now, I find it difficult to let go.”

The first Chinese characters she learned in school were “毛主席万岁” (Long live Chairman Mao) and “共产党万岁” (Long live Communist Party). She didn’t comprehend the meaning behind these characters, but she was always at the top of her class and never talked back to her teacher. Luo was a typical good student in the Chinese educational system. In elementary school, she was among the first to proudly wear the red scarf of the Young Pioneers, and in junior high school, she was part of the first wave to join the Communist Youth League of China. These political advancements were regarded as accolades bestowed upon obedient and academically successful students.

“I was indeed an obedient and well-behaved girl,” Luo chuckled. “When the teacher assigned the class to write a phrase one hundred times as a punishment, I diligently complied. My mom used to say that I treated every word from my teacher as if it came from the emperor."

V.

Luo Shengchun was only seven years old when Chairman Mao Zedong died in 1976. She observed the people around her engulfed in howls and wails of grief, seemingly devastated by the news. Why are they crying? she thought. And who is this person?

“You know Chairman Mao?” others asked through tears. “How could he be dead? He cannot die!”

Not sure what better to do, Luo mustered some feigned tears and joined the mourning crowd.

From a young age, Luo’s mother had instilled in her the importance of avoiding discussions of national affairs and steering clear of politics. She believed that one needed to follow the adage of “closing both ears to external matters, and dedicating oneself to the study of sage books.” Upon entering high school, Luo chose the science track instead of the humanities track. Despite her deep interest in literature, Luo believed that pursuing literature was a luxury she couldn’t afford. Studying science would help her to secure a stable income for her family.

In the spring of 1989, when Luo was a junior at Dalian University of Technology Power Engineering Department, waves of student protests erupted in Beijing. The April 27th Mass Demonstration, joined by thousands of people, the students’ hunger strike, and slogans of “We Want Freedom!” “We Want Democracy!” and “We Want Human Rights!” reverberated from Beijing to the rest of the country, including Luo’s school.

Having read through literature that reflected on the Cultural Revolution, Luo almost immediately identified with the values of this movement. She was always the first to join the local protests and the last to leave, leading from the front, and even helped make signs and chant slogans. Unlike many other students who believed that traveling to Beijing to show solidarity and support was crucial, Luo thought that for the movement to have a truly transformative impact, it needed to mobilize the masses nationwide.

Back then, Luo was unsure of the exact events that unfolded in the early hours of June 4, where hundreds of students and civilians lost their lives in the face of military tanks and gunfire. She imagined there were guns. It was not until years later when she came across the images of tanks crushing unarmed protesters. She decided to halt her activism in Dalian, and at the same time, set her sights on pursuing her graduate study in Beijing and uncovering the truth for herself.

When Luo arrived in Beijing in 1990, discussions of June 4 were strictly prohibited. Consumed by academic pressure, she gradually pushed the pursuit of truth to the back of her mind. However, deep within her, there remained a lingering sense of doom regarding China’s future. She diligently studied English. She yearned to study abroad and see the bigger world.

That is, until she met Ding Jiaxi in 1992.

VI.

After they started dating, the first question Luo asked Ding was why he wanted to be a lawyer.

“I’ve seen many people who couldn’t speak for themselves since I was young,” Ding said. “I want to be a lawyer so that I can speak up for them. There are so many ugly things in society that I want to change. I’m going to be a lawyer first, and then a judge, and then I’ll establish a more comprehensive legal system.”

Luo found Ding to be very ambitious. He was the only person she knew who would engage in discussions about these grand social ideals. Back then, Luo didn’t have her own idealism, but she found joy in listening to Ding talk about his dreams of a free, democratic society, gazing at him in admiration like an eager elementary school student. Luo remembered his words about how the imperial system in China had never truly come to an end, and that one of his favorite books was “Doctor Zhivago” for its insights of the essence of human nature and marriage.

She also shared a concern for society. When she walked past the homeless people on the street, she felt embarrassed by her inability to help, yet wondered why the government seemed to be providing little assistance to these vulnerable citizens. Before college, she had wanted to become a teacher and bring education to the most impoverished areas of China. During her annual family dinners, discussions would revolve around recent incidents of injustice that they had heard or witnessed. However, she thought no one expressed their thoughts as eloquently as Ding did.

At that time, she never associated Ding’s vision with politics in the real world, nor did she ever imagine that one day their family would suffer along with his pursuit of civil society. The 24-year old Luo knew only that she loved Ding's idealism and optimistic nature. She felt that she would do anything to support him, and she suspended her plan to study abroad.

Occasionally, she would ask Ding, “Honey, aren’t you exhausted from having all those thoughts swirling in your head all day? Can’t you just relax and enjoy a good life with me?”

“When we enter this world, we’ve got to leave our mark, you know?” Ding would reply. “Otherwise, what’s the point of being here? We’ve got to do something to make a difference, to contribute to the world’s progress.”

What’s the point of being here? This question has lingered in Luo’s mind since childhood. In the first two decades of her marriage, she believed her purpose was to support Ding and their family, to be a good wife, a good mother.

VII.

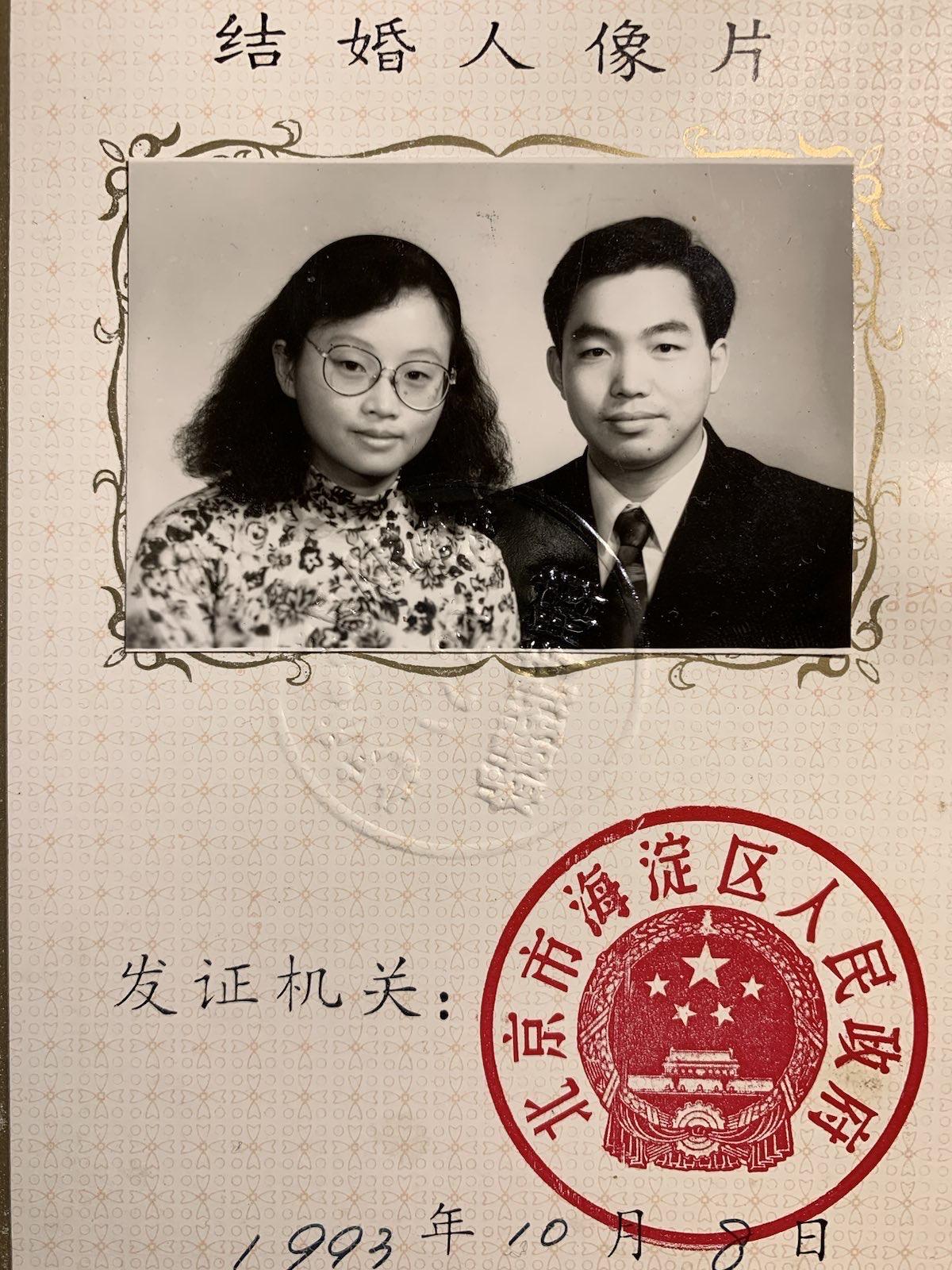

On October 8, 1993, Ding and Luo officially registered their marriage at the Civil Affairs Bureau. Just like many young couples in the 90s, they couldn’t afford an extravagant wedding ceremony with a grand banquet and a lavish wedding gown. Instead, they celebrated by sharing a bag of candies with Luo’s colleagues at the 304 Institute. They also took a simple black-and-white wedding photo at the Civil Affairs Bureau to put on their marriage certificate. Ding was dressed in a suit that Luo had bought for him with her first month's salary, while Luo, dressed in a floral outfit, wore a pair of round glasses and had shoulder-length curly hair.

The Marriage Certificate of Luo Shengchun and Ding Jiaxi, issued on October 8th, 1993

Shortly after their marriage, Ding was also accepted into 304 Institute. In the beginning, their limited budget allowed Ding and Luo to furnish their room with only essential items: a bed, a wardrobe, a television, a table, and a chair. Two years later, when Luo became pregnant, Ding set up a street stall for legal consulting and handed all his earnings to Luo as “formula milk money.”

“We really had to split every penny in half to make ends meet,” Luo said.

Luo didn’t ask for much, whether materially or emotionally. “I’m the kind of person who healed the scars and forgot the pain,” she said. Luo had to sign the consent form with her own trembling hands and undergo the C-Section alone. When Ding finally arrived at the hospital, their first daughter Katherine had already been born. They couldn’t afford a private ward at the time, so Ding had to leave in the evening. Still, when she saw him the next day, carrying a pot of chicken soup and stewed mushrooms, all her grievances disappeared.

Two months after giving birth, Luo returned to work. She enjoyed the daily routines of dropping off and picking up Katherine with Ding at the kindergarten provided by the institute. In 1997, Ding started to work at a program called the Lawyer’s Mailbox at the Central People’s Broadcasting Station, where he responded to over 140 letters from the audience, addressing various legal cases. In the 2017 interview with China Change, Ding said it was a good practice for his professional skills as a lawyer.

October 1997, Luo Shengchun and Ding Jiaxi with their elder daughter at Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China

Things were easy and stable. Those years were the happiest time in Luo's marriage.

VIII.

Around 2000, the seventh year of Luo and Ding’s marriage, Luo felt that Ding’s passion shifted away from her to his career ambitions. He wanted to make as much money as possible in a short period of time, so that after providing financial security for their family, he could be liberated to fully dedicate himself to the social movement.

While Ding toiled away late into the night, Luo sat at home, plagued by thoughts of his being unfaithful. She couldn’t trace the source of her suspicions, but a deep-rooted fear lingered within her—that one day, Ding would fall out of love, betray her, and abandon her. She incessantly questioned him who he was with and what he was doing. She was aware that her constant probing wearied him, and she sensed that their marriage had transformed into a burden for him.

“His focus was on work, while mine was on him,” Luo sighed. “It’s foolish and pathetic. I love him so deeply, and that’s precisely why I need to distance myself from him for a while.”

Luo made the difficult decision that a temporary separation might be the best for both of them. The longing to study abroad and experience the world outside of China, a dream she had set aside upon her marriage, now resurfaced. She dusted off her GRE books and began preparing for the exam once again. Ding gladly supported her decision and encouraged her to experience the world. This response, Luo believed, was partially rooted in his own vanity, a desire to have a wife who had studied abroad, who could “grace the grand hall and master the kitchen,” a common social expectation placed upon women in China.

In the fall of 2000, on a full scholarship, Luo arrived at Alfred University. The school was situated in Alfred, a charming college town in New York with a population of around 4,000 residents. She quickly fell in love with her new life in the United States, especially the freedom and the friendliness she experienced. She explored local churches, seeking solace from the stark atheism instilled in her since elementary school, and as she listened to the pastor's sermons and perused the pages of the Bible, she found herself resonating with the emphasis on family values and experiencing a newfound inner tranquility.

In the following winter, Ding brought their five-year-old daughter Katherine to visit Luo in Alfred. The winters in Alfred were bitterly cold, with thick blankets of snow enveloping the town, so when Luo attended her classes, Ding and Katherine indulged in skiing in the winter wonderland.

In 2001, Luo became pregnant with their second child, Caroline.

During those visits, Ding often went to the court hearings in nearby towns to observe the legal proceedings. He was eager to understand the American judicial system, and when he came home, he would excitedly share his insights with Luo. She appreciated every moment when Ding came to see her and made an effort to bring joy into her life. There was sweetness in simply listening to him passionately discuss his ideas on reforming the Chinese legal system based on the American model.

“I felt like an ugly duckling in front of him, but I wanted to transform myself into a beautiful swan. I wanted to grow and change on my own,” Luo said. “I felt that he was always educating me, always guiding me like a teacher, whereas I just wholeheartedly loved him. He knew he was my entire world, and I was just a part of his.”

IX.

In 2013, upon hearing the verdict sentencing Ding to three and a half years in prison, Luo’s first thought was that their marriage would once again be teetering on the brink of collapse.

She feared the idea of three and a half years of separation. In 2003, after watching the film “Cell Phone,” which depicted a couple’s breakup due to infidelity, Ding told Luo that while people often attribute divorce to the involvement of a third person, love itself can also be a cause for the dissolution of a marriage.

“I really do love you, but I don’t think you should return to China,” Ding said. “Why would you? You're so happy in the U.S. You wouldn’t be able to adapt to life in China anymore. There’s no room for the same level of freedom here.”

“You should stay,” Ding continued. “But I want to change China. I need to be on the ground.”

Luo was devastated. How could he say such a thing? Following that conversation, Ding rarely contacted Luo. She could sense that he was intentionally creating distance between them.

Luo wasn’t ready to leave the U.S. After graduating from Alfred University, Luo enjoyed her time working at the French multinational company Alstom. But she sensed that Ding, like a tree, was firmly rooting himself in the soil of China. In 2003, Ding and his colleagues founded the Dehong Law Firm in Beijing, and the firm grew rapidly. Luo felt that her destiny was calling for her to go back to China and be with Ding.

When Luo returned to China in 2004, Ding had already grown accustomed to being alone. He was cold as stone, and at one point, he told Luo that “I no longer have any feelings for you after those three and a half years of separation.” He moved out for a few months, and even when he returned, he seemed more engrossed in his golf and books than in engaging with Luo.

Luo put her work on hold for six months, hoping to focus on taking care of Ding and their daughters while readjusting herself to Chinese society. Social norms in China felt foreign to her. People weren’t used to saying or hearing “thank you.” Attending churches in China and reading the Bible in her native language could not bring her the spiritual connection. Amidst these challenges, she found herself deeply occupied with planning the interior design of an apartment that she and Ding had acquired, a space Ding stayed to avoid her once it was completed.

Ding frequently broached the topic of divorce, but Luo couldn’t fathom how one could express love through such a concept.

“Please, I beg you to stop these hurtful words,” Luo pleaded with him. “I would never even think about leaving you, even in the most difficult times. All I want is to have you right beside me. I don’t need anything else. You are the source of my happiness. Just you, being with me, that’s all I need.”

Luo believed that her words had somehow touched Ding. He stopped bringing up the topic of divorce and gradually became less indifferent towards her. Though the passionate love they once had was no longer there, Luo thought that at least they had regained a sense of familial affection. For Luo, the following ten years were peaceful and happy. She had successive promotions at her company, her husband’s law firm was thriving, and their two daughters were growing up well. She felt incredibly content.

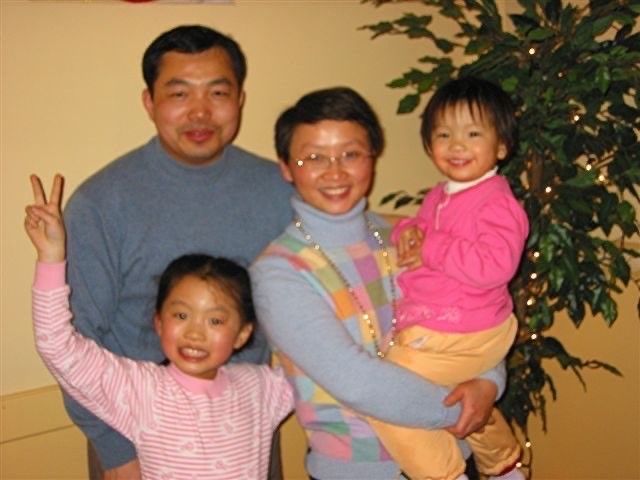

February 2004, taken at the house of Ding Jiaxi and Luo Shengchun’s friend in Alfred, when Jiaxi visited with their two daughters before Luo moved back to China.

X.

In October 2011, Ding returned to China from his visiting scholar program at Fordham University Law School. He met with Xu Zhiyong, a prominent civil rights activist and essayist, and started to attend a weekly constitution discussion seminar organized by several lawyers and scholars.

Led with the slogan of “Freedom, Justice, and Love,” the New Citizens Movement put forward two demands: first, that China would peacefully transition to a constitutional government, and second, that the society would transition from a feudal society to a civil society. In May 2012, the movement started to organize numerous same-city New Citizens meal gatherings, where people could meet and discuss political and civil topics. Ding was one of the main organizers behind this.

Luo instinctively agreed with the core value of this movement, but doubted how successful this New Citizens Movement would be.

“The purpose of CCP is to atomize everyone,” Ding said to her.

“Yes, I know that, it’s an obvious fact,” Luo replied. “I know once the citizens unite that could be a tremendous force. But do you think you really can unite everyone?”

“Don’t worry,” Ding said confidently. “Let me handle it one by one.”

Within a few months, Luo remembers, over twenty cities had citizen gatherings due to the influence of the New Citizens Movement. In September 2012, their primary agenda was to advocate for legislation mandating government officials’ property disclosure by the National People’s Congress. According to Ding’s address at a 2012 gathering, they made extensive efforts to promote the disclosure of officials’ assets. They distributed hundreds of thousands of leaflets, created over a hundred banners, organized two street protests, gathered over seven thousand signatures, and formally requested legislation on property disclosure from the National People’s Congress and the Legal Affairs Office.

Luo was interested in those New Citizens meal gatherings, but as Ding was occupied with connecting people all around China, she had to take up domestic duties. She went grocery shopping, prepared meals, cleaned the house, took care of her mother-in-law, and sent her two daughters to piano lessons, ping-pong and swimming practices. Although Luo wanted to go to one of their events and discuss her rights as a citizen, she never did. Before she became a New Citizen, she first had to be a mother and a wife.

XI.

On the night of April 17, 2013, the police came to Luo’s apartment. She tried to take pictures of them until they warned Ding to pacify her or face the consequences. Anger, helplessness, and confusion. Luo stood in silence as the police combed through their books, papers, photographs, and CDs, searching under beds, inside cabinets, and across their computer files. She insisted on going with Ding as the police continued to search his office.

Before the police took Ding away, he held Luo in his arms. “Go home, my wife, it wouldn’t do you any good for being here” and he secretly passed a note to Luo.

“Don’t worry, my wife,” Ding said, trying to sound as calm as possible. “Have faith in me.”

Luo couldn’t recall how she managed to make it back home. She was still trembling when she arrived. They had just gone to the U.S. embassy to apply for a visa the day before Ding’s arrest. Ever since Ding demanded public disclosure of government officials’ assets four months earlier, he had been under police surveillance and summoned for multiple interrogations, one of which lasted for 48 hours. He warned Luo that his activities had become increasingly dangerous and urged her to take their daughters with her and move to the U.S. for safety. Luo agreed, but she never anticipated that Ding would be arrested one day, and definitely not so soon. Ding had promised to join her in the States for a while to help her settle down, and she hung on to the optimistic thought that perhaps she could persuade him to stay in the U.S. and start a new life with her and the children.

“See, I told you I’ll be fine,” Ding reassured Luo after his first interrogation. “I lectured them for ten hours. They were like students in a class. Maybe they didn’t fully understand me, but I still had to share the idea of a civil society with them.”

Luo couldn’t share Ding’s excitement about haranguing the police. “I was scared to death.”

“Trust me. Your man is all about positive vibes!” Ding replied confidently. Luo couldn’t detect any signs of exhaustion in Ding, even after hours of interrogation. His confidence temporarily reassured her.

Luo supported the idea of the New Citizens Movement, but she found it difficult to accept that it was her Jiaxi who was taking such risks to advance it. When Luo and Ding’s families attempted to persuade him to choose a less dangerous path, Ding always countered with, “Why do you not try persuading the bad guys to stop doing bad things, but instead tell the good guys to stop doing good things?”

When Luo returned to their apartment in a mess, she noticed the police left out a few shirts with the New Citizens Movement slogan, “Freedom, Justice, and Love.” She thought she should alert someone about Ding’s arrest. She opened Ding’s note, and there were two names: “Liang Xiaojun,” a human rights lawyer, and “Wang Gongquan,” an entrepreneur who supported the New Citizens Movement.

The following days felt like a montage. At first, she didn’t cry. She still went to work the next day as usual. When she received Ding’s notice of criminal detention, she naturally asked the lawyer “Are they really not allowing him to come back?” A few days after Ding’s detention, she drove a group of lawyers who wanted to visit Ding to the detention center. The lawyers were impressed by her calmness.

“Well, I’m just eager to see my husband,” Luo said.

“You really don’t know?” the lawyers asked, taken aback. “You won't be able to see him, not for a very long time.”

In China, individuals undergoing criminal detention are prohibited from receiving family visits and are only permitted visits from lawyers.

Luo wanted to confront and argue with the people who had taken Ding away from her. She wanted to sit in front of the detention center in silent protest, to bring her mother-in-law and daughters to sit in front of the detention center with her. Eventually she did none of those things, with the memory of her father’s ordeal during the Cultural Revolution reminding her of the mercilessness of the authorities.

After Ding’s detention, Luo spent every day drowning in her tears. She couldn’t accept the fact that Ding had vanished from her life, that she could no longer talk to him, that she must live her life without his bright smile.

Later on, she met with Wang Gongquan in the park. Wang related to her the instructions left by Ding: if Ding was arrested, and if Luo didn’t want to endure the constant harassment by the police, she should get a visa as soon as possible and bring their daughters to the United States.

“Maintain a low profile while still in China and don’t let yourself and the kids in a situation like that of Liu Xia.” Luo recalled Wang’s warning, but saw no chance of Ding coming home early if she continued to stay silent in China for the sake of her daughters and herself.

Perhaps now was the time to go to the United States, she thought, where there might be hope for rescuing Ding.

On June 5, 2013, Luo obtained her visa and immediately booked a flight to the United States in four days. For four days she packed her belongings day and night. She had shipped everything she found remotely meaningful in their old apartment to the States – her graduation certificate, marriage certificate, Ding’s suits, the expensive outfits Ding bought for her, her daughters’ certificates of merits, toys and transcripts.

Luo knew this would be her farewell to China.

XII.

After Ding’s arrest, Luo’s eldest daughter Katherine bought Luo a bouquet of flowers on Mother’s Day. She then went to Hong Kong to take the SAT exam, where the parents of her classmates did their best to take care of her. They couldn’t believe it when they heard about Ding’s arrest, saying, “It can't be true. Ding is such a good person. It must be a mistake.”

It was only after years that Luo learned that Katherine couldn’t understand her father’s actions during that time. She was crying every day in high school in secret as she didn’t want to expose her vulnerability in front of her classmates. She believed that he didn’t love her mother, nor did he love her and her younger sister. She felt sorry for herself and her mother.

According to Luo, both of her daughters have endured psychological trauma because of Ding’s absence in their upbringing. Katherine has refused to read any letters written by Ding. “I didn’t know how to approach the subject of their father with them,” Luo confessed. Throughout the years, her greatest regret has been her relationship with her daughters.

Katherine and Caroline declined to be interviewed for the Reuters’ profile on Ding Jiaxi. Upon discussion with Luo, I decided to not reach out to them for comment by the time of publication.

XIII.

Luo didn’t want her neighbors in Alfred to think of her as a single mother. She feared this label would set her apart, making her seem peculiar or somehow lesser, so she consistently made a conscious effort to inform others that she indeed had a husband. She hated it when others inquired regarding Ding’s whereabouts, but she tried to answer with the most cheerful tone that he was occupied with his business in China but made regular visits to be with them.

In the initial six months of her relocation, Luo found herself unable to participate in any form of entertainment – movies, novels, or music – as each one served as a poignant reminder of Ding. Often, Luo was haunted by the thoughts of escaping this world, yet the sight of her daughters pulled her back from the edge of suicide, reminding her of the unfinished responsibility as a mother. She tried not to cry in front of them. She had to compose herself and stay focused on her daily work, secure a home, a car, enroll her daughters in school, transition herself culturally to the States, and apply for political asylum.

On top of the hustle, Luo reminded herself that Ding must come home: This is why I left China, to secure a safer environment for myself and my daughters, so that I could be a stronger advocate for Ding’s cause.

In July, Luo wrote an open letter to Beijing Procuratorate,“I am an ordinary wife who has shared twenty years of life with Ding Jiaxi. I know my husband has not committed any crime and was incapable of doing so. All he possessed was a fervent love for his country and the conscience of an ordinary person… If my husband truly committed any crime, I requested you to inform me, my lawyers, and all the concerned family and friends, without trying to silence public outcry by deleting online voices or comments that demanded justice for Ding.”

“My husband has always been honest and genuine in his dealings,” Luo wrote, “and I hoped the Procuratorate would do the same.”

As Luo was working with Jiaxi's friends to raise Ding’s case, she began to make a daily commitment to follow the news, and pondered the values he once emphasized: “freedom, justice, and love.”

“I began, just as Jiaxi had advised, to embrace the pursuit of democracy and freedom as a way of life, making it a part of my daily routine,” Luo said.

Luo said her transformation started from one simple idea: she knew who her husband was – an upright and principled Chinese lawyer who cared about the future of China. And if someone as generous and kind as Ding could be arrested by the authorities, then there must be something fundamentally wrong within the country.

In 2014, when Luo accepted the 28th Outstanding Democratic Activist Award by the China Democracy Education Foundation on behalf of Ding, she gave the following speech:

“Ever since Jiaxi was arrested, it feels as if I have opened my eyes for the first time to see a real China – the great country we were taught about in our childhood textbooks, the harmonious nation with stable democracy and the rule of law propagated in today’s Chinese newspapers. But actually, she is being humiliated by tyranny, ruled by oppression. Her officials are corrupted without bounds. Her children on this land are constantly threatened with illiteracy, drug abuse, and the possibility of being raped. Her people's homes are plundered, their land seized. They are beaten on the streets, tortured in black jails, and subjected to constant surveillance, tracking, and unwarranted searches. The mouths of her citizens are directly or indirectly sealed, only allowed to be silent and compliant like pigs content with three meals a day. The so-called Chinese Dream is nothing but a nightmarish creation by the Chinese authorities, who have no lack of excuses to inflict their wickedness upon us. What I see is not my beloved motherland; what I see is unmistakably a colossal prison!”

In the rare moments of solitude, she would write to Ding while imagining herself across from him during a prison visit. In their correspondence, Ding assured her that he was eating well, sleeping soundly, and even continuing to work out while incarcerated. He had plenty of time to read whatever books were available to him and delved into profound questions about the human body, nature, society, and existence. In March 2015, Ding even wrote down his contemplations on 36 questions, ranging from “How can humans understand the world?” and “Will religion fade away?” to “Can we eliminate war?” and “Will democracy become the prevailing global system?” and shared them with his daughter Katherine. Luo was relieved; it seemed as if the moment he entered prison, he had instantaneously “attained Buddhahood” and made peace with his situation.

“In these three and half years, I withered when his letters didn’t arrive,” Luo said. She listened to the audio recording of Ding’s message brought out by his lawyer again and again and transcribed them into articles for publication. “But whenever I heard his voice or read his words, it made me alive once again.”

XIV.

On March 15, 2014, two weeks after being in critical condition, Luo’s mother fell into a coma for several days.

After receiving the message from her brother, Luo dashed through the snow early in the morning. The chilling wind brushed past her ears. Her thoughts drifted back to her mother, who had single-handedly raised six children while her husband endured exile in a remote labor camp for a decade.

Now, I, as her daughter, she thought, accompanied by her two granddaughters, also endure the painful wait for my innocent husband. Six decades have passed, and history is repeating itself.

Luo yearned to return to China and visit her mother one final time. She knew that her mother’s biggest concern in her last days was for her and Ding. However, she couldn’t take the risk. What if I couldn’t return to the U.S.? she thought. What would happen to my children in that situation? She prayed for her mother’s forgiveness, and went to bed with a heavy heart, hoping that her mother would bid her a farewell in her dream.

The next day, she was notified that her mother had passed away.

“Mom didn’t appear in my dreams. She must have been mad at me for not coming home to see her. My heart is aching and numbing.” Luo wrote in her diary. “Being in church this morning, I imagined my mom was in heaven listening to me sing songs of Christ, and would understand how painfully and powerlessly I missed her. I repented for my failure of family responsibilities.”

During her graduate studies at Alfred University, Luo had converted to Christianity. She had been grappling with the meaning of the world and life since young, and once she read the Bible, she connected with its core teaching: honesty, kindness, the value of family, and most importantly, the fact that we all have sinned and need to repent.

At times, she found herself pondering why the all-powerful God didn't simply eliminate the CCP and all the injustices prevailing in the world. She questioned why, knowing the depth of her love for Ding, God would allow her to endure such struggles and uncertainties in their relationship.

Luo told me recently that she was inspired by the story of Exodus. When Moses tried to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, their initial reactions were filled with doubt, fear, and complaints due to their long-standing oppression. Some hesitated to believe him, while others grumbled during their journey through the wilderness. She contemplated that perhaps China needed to undergo the harrowing experience of dictatorship to truly value democracy, just as she needed to endure the pain of separation from Ding before fully savoring the sweetness of their love.

XV.

February 15, 2014, Saturday:

It's been almost ten months since you were imprisoned, and I've been in the United States for a solid eight months. I think I’ve done a pretty good job. I've managed to build a home, settle the children, and organize my work to the point where I no longer need to carry a pile of things home every day. We should’ve done something meaningful on the past Valentine’s Days. This morning, while running with Caroline, I decided to start keeping a diary. Since you continue to haunt my heart, perhaps having you before my eyes and engaging in a dialogue with you every day could be the best way to endure these difficult times.

February 18, 2014, Tuesday:

Today, after taking the children to their violin lessons and returning home, I suddenly felt incredibly unhappy… I feel uncomfortable every time I prepare documents for the asylum application, knowing that your hard-earned qualifications and practicing license as a lawyer will be revoked from the day of your conviction. It’s a feeling of regret, a feeling of knowing the consequences but unable to change the past.

The plumbing still hasn’t been fixed. I doubt it will be fixed by tomorrow. The feeling of not having anyone to consult about anything made me burst into tears.

I want to check WeChat, but at the same time, I dread it. Whenever I do check, I’m left disappointed. Truly, besides a limited few within your circle, many people simply don’t care. They don’t understand democracy, and they can’t make a living out of it. To them, why bother with democracy when losing their freedom for the sake of freedom seems like a self-inflicted punishment.

February 25, 2014, Tuesday:

You, with your magnanimous nature, always consider others and their needs, yet you chose me, a woman who simply desires your undivided attention… You will never change for me, but God demands that I change for you. Isn’t that somewhat unfair of God?

March 24, 2014, Monday:

[A journalist] called me and said that she wanted to interview me. Despite having a pile of work to tackle today, I agreed without hesitation. Was it an irrational decision? Our conversation stretched on for two hours, and I told her many stories about you and me that I had never before shared with anyone. After the call ended, I found myself wide awake. I miss you so, so much. I wonder if you would mind me discussing our love story and everyday life details with others. I hope you won’t take offense.

I once told someone that I came into this world to love you, but when asked if I believe that Ding Jiaxi also thinks of us and loves us every day, I surprisingly lacked the confidence to answer yes. I still feel that you care more about others than about us, that you prioritize society over our family. Is it true? You came into this world not solely for us, but for something else, right?

April 23, 2014, Wednesday:

In these three years, I will manage to keep everything in order. I will participate in various activities that make me happy, and I will try my best to take care of myself, although it is undeniably challenging because I cannot let go of the hopeless love for you. Each day, I will feel fulfilled, and I will even laugh out loud, leaving no trace of sadness. But I truly cannot find a shred of happiness anymore…

It has been a whole year, and to be honest, I am deeply unhappy and far from feeling content. Since you’re so smart, could you teach me: how can I navigate through the remaining two years without you?

May 25, 2014, Sunday:

Last weekend, the university was on break, and the village was strangely quiet. I suddenly felt a deep sense of depression, as if life had lost its meaning and hope. Despite the comforting words from friends at church, all I could do was cry.

This week, by a chance encounter, I came across a song titled “Amazing Grace,” which speaks of God’s immense love. I listened to it while going about my tasks, and I found myself listening to it for the entire evening. It sparked deep contemplation within me, and I felt like I suddenly understood many things. I have decided to dive into reading the Bible more attentively. I have always felt that I am under God’s protection, and I am sincerely grateful for this.

June 22, 2014, Sunday:

My dear politician, I understand that even if you were in the United States and your ideals were not realized, you would still feel imprisoned. I don’t want to turn our home into your prison!

August 19, 2014, Tuesday:

Today’s work tasks involve delving into the meticulous realm of project financials, urging myself to learn to like financial management. Additionally, I need to measure Katherine’s blanket to prepare for sewing a new cover and chair cushion for her.

September 16, 2014, Sunday:

In the blink of an eye, nearly a month has passed since I last received a letter from you. Every day, I eagerly wait for your response, but to no avail. Have you read the letter I wrote to you? Why haven’t I received any word from you? Is it inconvenient for you to communicate? Did I say too much in my letter to you? Are you unwilling to let me know about your situation in prison? Or perhaps the prison simply did not deliver my letter to you?

October 12, 2014, Sunday:

This morning, I spent some time browsing Twitter before getting up to go for a run. As I jogged, I thought I truly am so busy now – I have to take over and embrace all aspects of life on your behalf: exercising, savoring delicious food, appreciating the beauty around me. I also have to continue advancing the cause of democracy for you. And let’s not forget studying the Bible together. In simple terms, I have to live a life meant for two people.

There’s no time left for hesitation or uncertainty. I feel a surge of energy propelling me forward, firing up every fiber of my body… At the end of the session, pastor Laurie DeMott mentioned that she wanted me to talk to the kids next week about China – about what's happening there now and the situation of your imprisonment. She urged me to share the true China with them. I immediately agreed. I feel it’s my duty to spread the truth, an obligation I cannot ignore.

November 7, 2014, Friday:

Work has been progressing relatively smoothly this week, so I decided to take it easy tonight. After dinner, I sat by the radiator and couldn't resist browsing through WeChat, Facebook, and Twitter. Although compared to other cases of “prisoner of conscience,” our situation may not be the worst, I still can’t help but feel that the past three and a half years have been incredibly unjust for you! Everything you did was to help the government, but those fools failed to understand and insisted on finding a pretext to lock you up.

From time to time, I feel an urge to gather all the families of prisoners of conscience and write a letter to Xi Jinping and those brainless fools in the central government, urging them to open their eyes and see the world, to wake up! They need to listen to the voice of history. The Hong Kong students’ Occupy Central movement is still enduring with difficulty, and I applaud Zhou Fengsuo for going to Hong Kong to support them. However, I still worry about their safety.

Tomorrow marks the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall… How much longer does China's authoritarian rule have to persist?

April 8, 2015, Wednesday:

I am actively studying basic financial concepts and learning how to file taxes, specifically understanding those concepts in English. I no longer procrastinate from this task like before. I used to have numerous sweet treats just to calm my mind while facing tax forms. But now, that is no longer necessary. Encourage me to continue striving and become the expert in our family, won’t you?

June 21, 2015, Sunday:

Feeling disheartened as my company has not assigned any projects for me to manage. To overcome this sense of disappointment and the anxiety for your letter, I decided to join Luanne in preparing for the choir performance on Alfred’s alumni day, which will take place on Saturday, June 13. We will be singing several quite difficult songs. Following the recordings, I have been practicing hard for almost an entire week. The melodies and lyrics of those songs are lingering in my head even now!

July 13, 2015, Monday:

This is a vast void,

It is present when I am joyful,

And it remains when I am not,

I cannot push it away, nor can I drive it out,

I strive to avoid stepping into this abyss,

With utmost caution,

Yet it lingers by my side,

What is it?

XVI.

In September 2017, Ding and Luo reunited at Greater Rochester International Airport. It felt like a dream to Luo. She didn’t bother with dressing up or putting on makeup, still uncertain if this moment was real as she made her way to the airport. As Ding opened the car door and got in, he greeted her with simple words, “Hello, my wife.” There were no embraces or handshakes, and during the entire journey back, they didn’t know what to say to each other.

Since Ding’s release in October 2016, his visa applications to visit the U.S. had been - rejected until September 2017. When he finally obtained the visa, he asked Luo to book a round-trip ticket. He intended to stay for only two months.

“I have waited for you for four years,” Luo pleaded Ding. “But you’re only willing to give me two months.”

During the initial days of their reunion, Luo felt disoriented in Ding’s company. She was afraid to be close to him, and didn’t know what to say. Slowly, she began to feel that Ding was no longer a stranger after four years apart; he was her husband, her Jiaxi again. However, simultaneously, she was painfully aware that she would soon have to part with him once again.

Luo said that during those two months, Ding embraced the role of a good husband and father. He took care of household chores, cooking, and laundry, impressively tidying up the house to the point where their daughters marveled at its newfound cleanliness. He joined her for walks, social gatherings, and church services, eager to meet everyone she knew. They danced together, attended art exhibitions, enjoyed music concerts, and walked along every hill in Alfred. He woke up early to practice yoga with her. September and October happened to be the most vibrant months in Alfred, and he accompanied her to experience every bit of it.

Luo shared that while Ding was here, he made progress in improving his relationship with Caroline. They played tennis together, and he even attended her tennis matches at school. However, Katherine still held a grudge against him. She was studying at Cornell when he visited, and they only managed to have a few meals together on campus.

September 2017, family reunion on the campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, NY.

At times, Luo found it difficult to tolerate the habits Ding had developed during his time in prison. He always wolfed down his food so quickly that Luo barely had time to sit down. His constant pacing and contemplation in the room made Luo feel dizzy. He found everything edible fascinating, even the simplest chocolate that Luo considered ordinary; he would want to buy it and give it a try. Luo wanted to say something, but then, considering they only had two months together, she decided to let it go. There was no point in trying to change his behaviors just for the sake of two months.

After staying together for over a month, Luo noticed that Ding started to appear absent-minded. He seemed restless, eager to return to China, as if he stayed any longer, he might not be able to go back.

“Why do you have to go back to China?” Luo challenged him. “As an individual, your power is limited. Only God can change China. You can stay in the U.S. and witness China’s transformation remotely.”

“I feel uneasy here,” Ding responded. “I’d be guilty if I’m here enjoying the life of freedom and democracy while one-point-four billion people in China suffer under authoritarianism and dictatorship. I can’t leave China.”

Every day, they talked about whether he should stay or leave, but Luo was aware that these discussions were futile. She knew she couldn’t force him to stay. She just wanted him to stay a bit longer. She envisioned him staying for two more months until Christmas, when their daughters would be on break. She thought it would be wonderful if he could spend Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year with them.

Luo remembered the time when Ding held her in one arm and Caroline in the other, saying, “Help me figure out how I can have it all. I’m torn in two. I want to be with you both, but my heart is in China.”

Luo said everyone that met Ding tried to persuade him to stay. Her colleagues at Alstom suggested extreme measures like hiding his passport, shredding it, or even burning it.

Luo made the difficult decision to let him go. She understood that if she forced him to stay, their home would become a prison for Ding.

“I thought God had destined him to return to China.” Luo told me.

Her daughters felt otherwise. According to Luo, Katherine would not forgive Ding. She thought Ding turned away from his family responsibilities and failed to be the father or husband this family needed. Caroline was reluctant to mention Ding in her college admission essay. She couldn’t understand why her father would say he loved them, but then chose to leave them for China.

In the end, only Luo drove to the Buffalo Airport to see Ding off. She watched as he waved her goodbye, swung his backpack over his shoulder, and blew her a kiss. “Go back, my dear wife. Everything will be fine,” he said with his ever radiant smile, and then disappeared from her sight.

Luo didn’t know how she drove back. She felt like a knife was cutting through her heart.

In May 2018, Ding wanted to visit for Katherine’s college graduation ceremony. He packed a suitcase full of their cherished memories from China – photo albums, clothes, and gifts he had bought for Luo and their daughters – but upon reaching the border, he was informed that he was on the travel ban list for national security reasons.

Ding and Luo were devastated. In the following week, during some sleepless nights, Ding gathered every photo they had together, refilmed them one by one and stored them on a USB drive, then arranged for someone to bring the USB to Luo.

Luo thought she might never see Ding again in her life. Her body experienced a stress response as the right half often felt as if it had been electrocuted. She believed this was because she no longer felt complete. She had lost a part of her life.

Once again, Ding brought up the idea that he wouldn’t blame Luo if she chose to get divorced and be with someone else. Hurt by his words, Luo implored him to stop saying such painful things.

“Just tell me when you will come home,” Luo pleaded.

After two weeks of contemplation, Ding finally responded, “Give me ten years, my dear wife, starting from the point I was released in 2016. If I cannot achieve my vision in ten years, I will come home to be with you and the kids. In 2026, if I fail, I will find a way to come to you, no matter what it takes, even if I have to leave by sneaking across the border.”

XVII.

According to the “12.26 Citizen Case” report by Human Rights in China, in early December 2019, legal advocate Xu Zhiyong, lawyers Ding Jiaxi and Chang Weiping, along with other lawyers and participants, gathered in Xiamen, Fujian Province, to engage in discussions about current affairs and China’s future, and exchanged their experiences in advocating for the development of civil society.

On December 26, the authorities initiated a crackdown on the participants and other individuals involved in the private gathering. Over 20 lawyers and other citizens were either taken away, summoned, or detained. Some were held under suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Many of those detained were later released on bail pending trial. Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi faced official arrests. Li Qiaochu, who publicly advocated for the release of her boyfriend Xu and others, was summoned for questioning multiple times and eventually detained at an undisclosed location. Lawyer Chang Weiping experienced two instances of residential surveillance at a undisclosed location, where he was subjected to torture, before he was officially arrested.

XVIII.

Many years ago, Luo and Ding had made a pact to visit Hawaii together, and Luo and her daughters had waited for Ding to join this trip since then. In the winter of 2019, they came to the realization that Ding might not be able to join them for a long time, so they set off to Hawaii without him.

On the eighth day of their vacation, while Luo was climbing a mountain on a coastal trail and her two daughters were playing in the water at the beach below, she received a phone call from a friend: On the night of the 26th, a group of police officers had forcibly taken Ding away along with his belongings without providing any legal documents, leaving broken security locks and his apartment in chaos.

Luo’s heart sank. Four hours before Ding’s arrest, Luo was still talking to him on the phone, asking him to try again to visit her in case he had already been removed from the travel ban list. She broke the news of Ding’s sudden arrest to her daughters. Shocked and enraged by the news, her daughters noticed afterwards that Luo was staring blankly, lost in her thoughts. They repeatedly asked her “Mom, are you okay?” but Luo didn’t know how to respond.

They flew back from Hawaii the next day. Luo reached out to her “709 sisters” – accidental activists in China, who had been advocating for their husbands that were taken away during the nationwide crackdown on human rights lawyers that started on July 9, 2015. The crackdown was later known as the “709 crackdown.”

“Please, teach me what to do,” Luo said to her 709 sisters. “I will not stay silent this time. The CCP has way crossed the line, and I have all my time and energy in the world to fight them.”

Her 709 sisters quickly pulled together a group chat and instructed Luo to raise Ding’s case through Twitter. Since Luo signed up for Twitter in 2014, she had only posted twice about her everyday life and once to support her 709 sisters. Luo initially wanted to post once every week, but they told her that she must post everyday. Now she needed to weave each sentence like delicate embroidery to articulate Ding’s case with utter clarity in a few hundred characters.

On January 6, 2020, Luo posted the first video shot by her daughter Caroline. In the video, Luo, dressed in a red turtleneck sweater, sat solemnly on the brown sofa in her home in Alfred, with a table lamp casting a soft glow on her. She announced the news that Ding Jiaxi had been missing for ten days.

“I know my husband very well. He is a gentle and rational person. Despite the thousands of miles between us, we communicate through video almost every day. I'm certain he hasn't done anything that violates the Chinese constitution or laws. On the contrary, it is illegal for the police to take my husband and all his belongings without presenting or sending any legal notice. I have hired a lawyer who will follow leads provided by friends and head to Yantai, Shandong, next Tuesday to find out what happened to my husband. I will continue to report my husband’s abduction by Chinese police to my friends and the international community. Thank you all.”

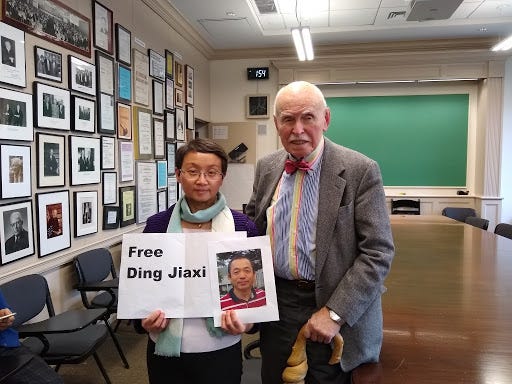

In January, Luo posted her interaction with seven officials at the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, Congressman Jim McGovern, Democrat, Massachusetts, and the founding director of NYU U.S.-Asia Law Institute, Jerome Cohen.

January 2020, with Dr. Jerome Cohen in a meeting room at New York University.

In February, she gave a speech at Alfred University on her family’s connection with Alfred, the crackdown on New Citizens Movement from 2013 to 2014, and Ding’s arrest over a gathering with friends in Xiamen.

In March, Caroline and Katherine each received nearly 30 letters and cards supporting Ding at their schools. Luo sent a petition letter requesting the release of Ding and his friends involved in 12.26 Citizen Case with 32 pages representing 329 signatures from six states in the United States, to Minister Zhao Kezhi of the Chinese Ministry of Public Security, Director Zhao Feng of Yantai Public Security Bureau, and Ambassador Cui Tiankai of the Chinese Embassy in the United States.

By the end of the year, she had sent out letters regarding the 12.26 Citizen Case to government officials and human rights organizations to over twenty countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania.

In 2022, Luo was invited to attend the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy, where she gave the speech “Losing My Husband to China” and implored the U.N. and the American government to “intervene and say – we know this is a fake case. Release them now or face sanctions.”

In April, 2022 in Geneva, Switzerland, speaking at the 14th Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy.

Locally, Luo’s friends at the Alfred Union University Church took action by creating eleven videos demanding the release of Ding and his colleagues. In September, the local newspaper, The Alfred Sun, showcased Luo's essay titled "Ding Jiaxi and Alfred," which was originally published in China Change in August, on the front page with a bold headline that read “Free Ding Jiaxi!”

XIX.

Soon after Ding was forcibly disappeared, Luo realized that this time was different from Ding’s first arrest. In 2013, a few days after Ding was taken away by the police, his lawyers were able to meet with him and bring out audio recordings regularly. Legal documents, from indictment to verdict, were delivered to Ding’s lawyers accordingly. From their communication during Ding’s time in prison and after his release, Luo knew that he wasn’t subjected to torture. While she remained convinced of the unjust nature of his sentence, there was solace in the knowledge that his time in confinement hadn’t been marred by severe suffering; he retained basic comforts—access to sustenance, hygiene, rest, reading, and contemplation.

This time Luo and the lawyers barely received legal documentation. Besides a handful of letters rejecting the lawyer’s request to meet with Ding over the excuse of his alleged involvement in “subversion of state power,” an official arrest notice was sent to Ding’s sister in June, 2020. For six months, Luo remained in the dark concerning Ding’s whereabouts and the reason behind his detention. She didn’t know if he was alive. It wasn’t until thirteen months into his detention that Ding was finally permitted to meet with lawyer Peng Jian. Yet this meeting came at the price of Peng being coerced into signing confidentiality agreements that precluded him from discussing Ding’s case with the media, or publicly addressing any aspects of the case.

Upon Luo’s request, I did not reach out to Peng for comment by the time of publication. According to Luo, agreeing to an interview with foreign media outlets would potentially lead to the suspension of Peng’s legal practice license.

In April, 2020, Luo started to write letters to Ding. She was proud that her letters were no longer filled with sorrow and grief, but instead brimming with her determination to fight.

In the beginning, she sent letters via text message to police officer Liu, who was in charge of contacting members of the arrested on behalf of Yantai Public Security Bureau, but received no response from him. For the first thirteen months of Ding’s arrest, he was deprived of the right to meet with a lawyer or correspond with Luo. Left with no other choice, she decided to make these letters public on Twitter and Facebook.

“I told Jiaxi how the pandemic wreaked havoc globally, starting from China.” Luo wrote in an article published on China Change in August, 2020. “I told him that his mother knows he is innocent and who the real culprits are. I told him how spring came late this year. I also told him how my children and I enjoyed our work and life during the pandemic. I told him the blooming forget-me-nots, peonies, orchids, and chives in our backyard. I hoped to share the beauty and hope in our lives with him.”

Luo wrote “May my letter be your sunshine” at the end of those letters.

XX.

On the 179th day of Ding’s arrest, Luo was jolted awake by a nightmare. In her dream, Jiaxi was subjected to such brutal torture that she could hardly recognize him. She couldn’t fathom the toll all the torture was taking on Ding. She prayed that God would watch over her Jiaxi.

After having been disappeared for 392 days, on January 21, 2021, from the Linshu County Detention Center in Linyi City, Shandong Province, Ding spoke to his lawyer Peng for the first time after his arrest via video. In their 30 minute video call, Ding said the following about the torture he experienced during Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location:

“It was in the deep winter when I was arrested. I only had one piece of clothing on me, and was taken away wearing just slippers on my bare feet. It was bitterly cold outside, and I felt like every joint in my body was being pierced by knives.

After the Spring Festival, the police started to play ‘Xi Jinping Governance Strategy: China’s Five Years’ to me on repeat, day and night, for 10 days at the maximum volume.

During my six months of Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, I made zero confession for the first one hundred and three days. For seventy three days I endured sleep deprivation and exhausting interrogations. I didn’t see a glimpse of sunlight for six months. I was under artificial lighting 24 hours per day. I was not allowed to bathe or brush my teeth…

…From April 1st to 8th, I was bound to a tiger bench, with a strap tightly restricting my back and another tightly constricting my waist, making it difficult to breathe. Each day, eight people in four shifts interrogated me from 9 a.m. until 6 a.m. the next day, continuously for 24 hours without allowing any sleep. On April 7th, my ankles swelled like buns, and the pain was unbearable. I suddenly thought of my wife and daughters, so I told the interrogators that I would no longer insist on making zero confession.”

Although Luo had expected torture, the gruesome details of their cruelty still managed to shock her deeply. “This regime has lost all semblance of humanity,” Luo thought, filled with dismay and horror. She realized that Ding's release was unlikely as long as the CCP remained in power.

In her next letter to Ding, she wrote, “My dear husband, rest assured, I will not let them get away with this. I won’t allow you to bear this pain in vain.”

Tears, sighs, and grief are futile. Luo realized. Only through struggle and fighting back can I save my Jiaxi.

XXI.

After Ding was able to meet with his lawyers, Luo started to have lawyers bring a letter to Ding and read it to him in every meeting. Other than sharing updates about her personal life with Ding, Luo also wrote to him about recent developments concerning other people involved in the 12.26 Citizen Case, as well as domestic and international news. From the outbreak of Covid-19, the murder of George Floyd, to Biden’s inauguration and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Luo made sure Ding had not fossilized in prison.

Meanwhile, Luo expanded the scope of her advocacy to human rights lawyers and activists involved in 12.26 Citizen Case, and later to the millions of Uyghurs being held in re-education camps, the imprisoned citizen journalists, and White Paper protesters.

In the lead-up to Ding’s sentence in April 2023, Luo chose to publicly present herself as an “amateur human rights defender,” the wife of Ding Jiaxi who aligned with his human rights advocacy. She deliberately refrained from positioning herself as explicitly “anti-CCP.” In the event that Ding decided to seek release by appealing to authorities, promising to abstain from political engagement as an exchange for reunion with his family, Luo wanted to ensure that her public stance was not perceived as a provocative antagonist by the regime and would not undermine his chances. In her correspondences with Ding, Luo frequently implored him to make these requests, which Ding always declined. He was confident that the CCP would crumble before he concluded his sentence.

Luo also once harbored hopes that the ascension of new leadership might usher in a potential turning point for Ding’s case. Yet, with Xi Jinping commencing his third term as the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2022, she realized that this glimmer of hope had all but faded away.

Since Ding was sentenced to 12 years in prison in April, 2023, Luo openly expressed her opposition to the CCP. She knows clearly that only if CCP is in power, Jiaxi has no chance to be back home. She said that she no longer felt sorrow or pain, as she had grown stronger by witnessing more darkness under the CCP everyday.

Luo said she wrote to Ding that she couldn’t go back to who she was before. Previously, her everyday life was to pursue human rights. Now, it was to overthrow the authoritarian regime of the Chinese Communist Party and pursue democracy, rule of law, and a free China.

In 2023, she attended the Captive Nations Summit at the Victims of Communism Museum in Washington, D.C. as a panelist on Global Voices of Freedom. At various platforms such as the New York Zephyr Society (formerly known as Democracy Salon), Cornell University, and the National Endowment for Democracy, Luo recounted Ding’s story. She wanted to bring attention to his case but, more crucially, to exemplify the alarming deterioration of human rights, and the complete lack of rule of law and freedom in China.

“The government accused Ding and Xu of subversion of state power without any evidence,” Luo told me. But now I am going to subvert the CCP with full ‘evidence’.”

According to Luo’s demand, the specifics of her plan in subverting CCP will not be disclosed in this article.

“I pray to God for granting me wisdom and strength to devote myself to the mission of this generation, and I call for solidarity of worldwide like-minded friends to take action together with me.” Luo declared firmly at the 2023 Captive Nations Summit in July. “Let’s end the CCP together in this generation!”

July 2023, at the Victims of Communism yearly Captive Nations Summit.

I attended two of these speeches, and I marveled at how Luo managed to compose herself so that she didn’t shed one tear. She only, and always, choked up when talking about her daughters.

XXII.

From Katherine to Ding in May, 2021: